Studio Hildebrand

Mag.Art. Christoph Hildebrand

+49 0163 5810594

ch@studio-hildebrand.net

Mag.Art. Christoph Hildebrand

+49 0163 5810594

ch@studio-hildebrand.net

Geschichte

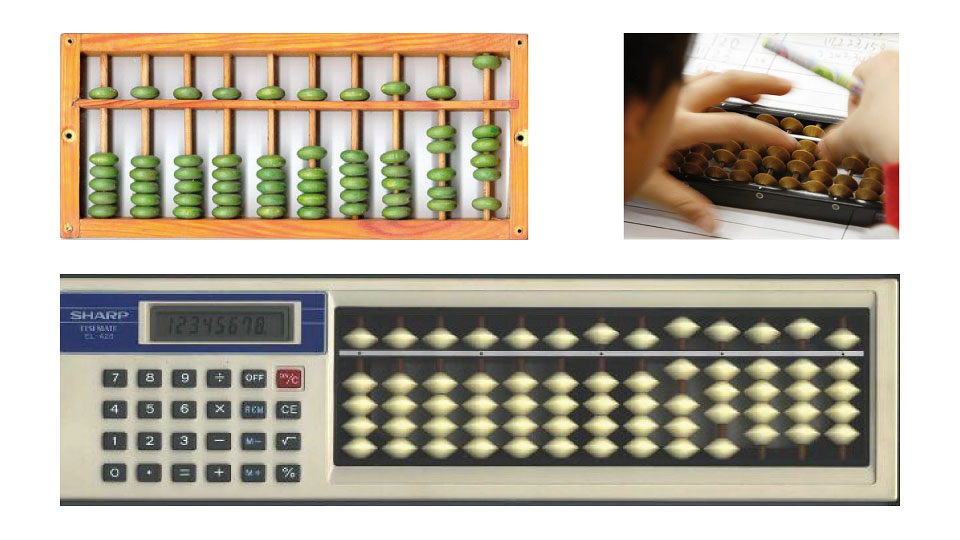

Der Abakus war das erste technische Hilfsmittel um Berechnungen zu erleichtern und ist damit der direkte Vorläufer des Computers. Konrad Zuse, nach dem das Institut benannt ist, baute 1938 die erste mechanische, funktionstüchtige, programmierbare Rechenmaschine auf digitaler Basis, später dann mit elektrischen und elektronischen Bauteilen. Er ist damit einer der Väter des Computers, wie er heute weltweit genutzt wird und nicht mehr wegzu-denken ist.

Strategie

Computer dienen schon seit vielen Jahren nicht nur mathematischen Zwecken. Der An-spruch ist vielmehr, die Welt als Gesamtes in all seinen Feinheiten und Verzweigungen im digitalem Code abzubilden, zu archivieren oder zu berechnen. Auch das Rechen- und Medienzentrum in Rostock soll seinen Beitrag dazu leisten.

Skulptur

Das vorgeschlagene Kunstwerk ABAKUS verknüpft das allbekannte Bild des Abakus mit dem archetypischen Bild der Weltkugel. Statt der üblichen Holzperlen ist der ins riesenhafte vergrößerte Abakus mit Erdgloben, Mondgloben und Sternengloben bestückt. Viele Aspekte im Kontext der Forschung und des Institutes werden damit angesprochen:

Kontext

Zuvorderst wird das Objekt des am Insitut getriebenen Rechenaufwandes formuliert: nichts weniger als – die Welt. Gleichzeitig verdeutlicht die Skulptur den Anspruch, dass dies auch allumfassenden gelingt. Die schiere Größe macht die gewaltige Rechenkraft sinnlich erfassbar und unterstreicht die emminente Bedeutung, die die Verarbeitung von Daten heute in der Welt hat. Durchaus auch kritisch wird in der Unterordnung der Globen in die Maschi-nerie des Abakus die Haltung angesprochen, dass die Welt als „technische Problem“ beherrschbar erscheint und vollständig funktionalisiert werden kann.

Rechnender Raum

Ein interessanter Nebenaspekt der Verwendung von Erd-, Mond- und Sternengloben ist der Verweis auf Konrad Zuses Hypothese des „Rechnenden Raums“. In seinem Spätwerk beschrieb Zuse 1969, dass der Kosmos selbst als gigantische Rechenmaschine aufgefasst werden könnte.

Soroban

Als Modell für den Abakus stand die Variante des Soroban, wie er heute noch im hochtechni-sierten Japan, trotz Taschenrechnern, vielfach im Gebrauch ist. Diese Form des Abakus ist besonders effizient in der benötigten Anzahl von Perlen.

Zahlen

Für die dargestellte Zahl möchte ich die Ziffern des Geburtsdatums von Konrad Zuse vorschlagen: 00.22.06.1910. Eine andere Idee ist die (zugegebenermaßen fiktive) Zahl der auf der Erde lebenden Menschen zum Zeitpunkt der Einweihung des Instituts, etwa: 7.012.349.658. Weitere Vorschläge sind willkommen.

//

History

The abacus was the first technical aid to facilitate calculations and is thus the direct precursor of the computer. Konrad Zuse, after whom the Institute is named, built the first mechanical, functional, programmable calculating machine on a digital basis in 1938, later with electrical and electronic components. He is thus one of the fathers of the computer, as it is used worldwide today and has become indispensable.

Strategy

For many years, computers have not only served mathematical purposes. The aim is rather to represent the world as a whole in all its intricacies and ramifications in digital code, to archive it or to calculate it. The Computing and Media Centre in Rostock is also to make its contribution to this.

Sculpture

The proposed artwork ABAKUS combines the well-known image of the abacus with the archetypal image of the globe. Instead of the usual wooden beads, the abacus, which has been enlarged to the size of a giant, is equipped with terrestrial globes, lunar globes and star globes. Many aspects in the context of research and the Institute are thus addressed:

Context

First of all, the object of the computational effort at the Institute is formulated: nothing less than – the world. At the same time, the sculpture makes clear the claim that this can be achieved in an all-encompassing way. The sheer size makes the enormous computing power sensually tangible and underlines the eminent importance that the processing of data has in the world today. The subordination of the globes to the machinery of the abacus also critically addresses the attitude that the world appears to be controllable as a „technical problem“ and can be completely functionalised.

Calculating space

An interesting secondary aspect of the use of terrestrial, lunar and stellar globes is the reference to Konrad Zuse’s hypothesis of „calculating space“. In his late work, Zuse described in 1969 that the cosmos itself could be conceived as a gigantic calculating machine.

Soroban

The model for the abacus was the variant of the soroban, as it is still widely used today in high-tech Japan, despite pocket calculators. This form of the abacus is particularly efficient in the number of beads required.

Numbers

For the number shown, I would like to suggest the digits of Konrad Zuse’s date of birth: 00.22.06.1910. Another idea is the (admittedly fictitious) number of people living on earth at the time of the inauguration of the institute, for example: 7,012,349,658. Further suggestions are welcome.

P R O P O S A L Competition Rechenzentrum "Konrad Zuse" Universität Rostock 2011 + D E S I G N 50 globes / LED / acrylic / aluminium / stainless steel / size 10.00 x 4.40 x 2.40m + S U P P O R T Institution Persons City + M E D I A 4 images © Christoph Hildebrand + T A G S LED / Neon / Urban / Proposal / +